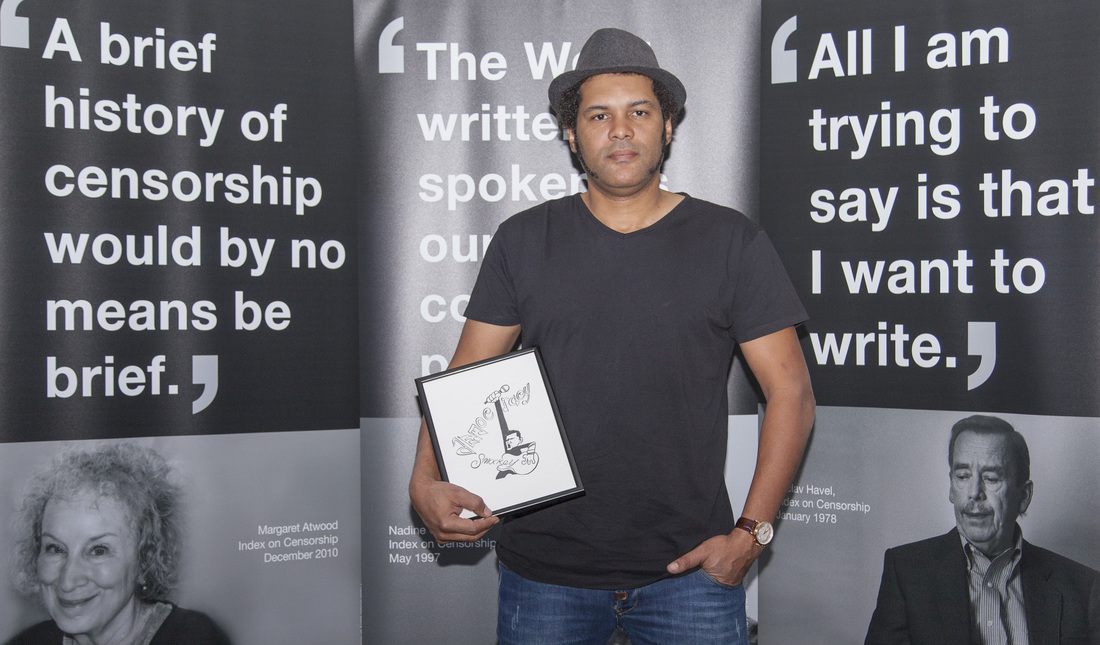

“Not everyone is lucky enough to have a microphone in front of them, so if you have the chance to talk, you have to say something important” Music and activism have strong connections and Serge Martin Bambara — aka "Smockey", meaning “se moquer”, or “to mock” – is the one of the most exciting performers merging the two today. 13th April marked the day Smockey became the inaugural Music in Exile fellow at the annual Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards at the Unicorn Theatre in London, with a live performance of his popular tracks. The award was presented by Martyn Ware, founder member of the Human League and Heaven 17. The hip-hop artist may be little known outside his home country, but he has had an impressive impact on political and social development in Burkina Faso, both through his music and campaigning. He has also suffered the destruction of his recording studio, the acclaimed Studio Abazon, which was firebombed during the attempted coup in September 2015. Soldiers fired two anti-tank rockets into the building, according to reports. Smockey combines rap with traditional Burkinabé music and humour to “spread truth”. “Knowledge is important, and I write as a way of presenting it to the people,” he told Index on Censorship. “Musicians often put their heads above the parapet to speak about issues that governments would rather ignore,” said Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of Index on Censorship. “Smockey has used his music to expose endemic corruption and fight for democracy. We are delighted to have him as the inaugural Music in Exile fellow.” The crowd-funded Music in Exile fellowship was launched in partnership with the team behind the new award-winning documentary covering threats to music in Mali, They Will Have To Kill Us First. The fellowship recognises musicians who perform despite enormous threats to their freedom. "We are so proud that Smockey has been announced as the first winner of the Music in Exile Fellowship. We started the Music in Exile Fund with Index on Censorship in order to empower other musicians who wanted their voices heard against oppression. The fund was possible due to the support of the audiences internationally who have donated generously after watching They Will Have To Kill Us First. We look forward to seeing Smockey grow further as an artist thanks to the support and guidance of the fellowship," said Sarah Mosses, producer of the film. Smockey first became interested in hip-hop music after listening to American artists like Public Enemy, Afrika Bambaataa and LL Cool J. He began rapping in Burkina Faso in 1988, before moving to France in 1991 to study. While there, he signed to the record label EMI, but it wasn’t until he returned to his country of birth on a holiday in 1999 that his music took on the political dimension it is famed for today. “It was around the time of the murder of journalist Norbert Zongo, who was assassinated following investigations into the activist by president Blaise Compaoré,” he said. “Student demonstrators were being beaten by police. It was very disturbing to me.” Smockey soon packed up his computer and keyboard in France and moved back home to Burkina Faso in 2001. “Seeing the things going on in my country, I had to do something,” he said. “At the time, I didn’t know exactly what, but I knew it would involve music.” “Not everyone is lucky enough to have a microphone in front of them, so if you have the chance to talk, you have to say something important,” Smockey said. This is the thinking behind subversive songs like Votez Pour Moi (about democracy), Tomber la Lame (FGM) and A Qui Profite le Crime (government corruption). In the summer of 2013, Smockey co-founded Le Balai Citoyen (The Citizen Broom) with reggae artist Sams’K Le Jah. The grass-roots movement was set up in opposition to then president Blaise Compaoré. Le Balai Citoyen played a big part in the ousting of Compaoré. It urged the people of Burkina Faso to organise and take to the streets. Following mass demonstrations in late 2014, Compaoré resigned on 31 October after 27 years in power. A transition government, led by the military, was established. However, a military coup saw General Gilbert Diendéré — leader of the Regiment of Presidential Security (RSP), Compaoré’s former secret service — seized power in September 2015. The Music in Exile Fund is a joint project launched by Index on Censorship and the producers of the award-winning They Will Have To Kill Us First, a documentary about musicians in Mali where music was banned. The Music in Exile Fund will contribute towards Index on Censorship’s Freedom of Expression Awards Fellowship, which is a year-long structured assistance programme to support those facing censorship. The money raised will be used to support at least one musician or group per year, beginning with Smockey. As the Music in Exile fellow, Smockey will receive training and opportunities to connect with other free speech heroes around the world. Index supports these activists with training on digital activism and other tools to stand up to the pressure of censorship and continue their battle for free expression around the world. The Index Freedom of Expression Awards recognise those individuals and groups making the greatest impact in tackling censorship worldwide. Established 16 years ago, the awards shine a light on work being undertaken in defence of free expression globally. All too often these stories go unnoticed or are ignored by the mainstream press.

0 Comments

|

If you enjoy reading this content, please consider a donation Donate© 2011-2024 Global Metal Apocalypse

Archives

November 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed